Sudeten German Weekend

Saturday-Sunday, September 24 & 25, 2022

In September 2022, the Island Church Foundation, Inc. will hold a Sudeten German Weekend which will provide an in-depth look at the history of a people that migrated twice, first from Germany to Bohemia, and then to Wisconsin. Key settlement areas of these Sudeten German were Jefferson, Dodge and Dane counties, Wisconsin.

The Sudeten German Weekend will focus on the earliest settlement area, which is in the Town of Waterloo, Jefferson County, Wisconsin. You will learn how poor Germans from Northeast Bohemia in the modern-day Czech Republic traveled thousands of miles from their long-time homes to the New World and settled on marginal farmland. You will tour two original pioneer structures, St. Wenceslaus Church (the so-called “Island Church”) and the log home of Vincent Faultersack.

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2022 – HISTORY SEMINAR – REGISTRATION REQUIRED

625 N. Monroe St., Waterloo, WI

8:30 – 9:00 a.m. Registration at the Karl Junginger Memorial Library in Waterloo, 625 N. Monroe St.

9:00 – 4:00 a.m. History Seminars:

Session One: The Story of Two Migrations – the German Migration to Bohemia and the German-Bohemian Migration to America by James E. Kleinschmidt, Bend, OR.

Session Two: German and Czech Emigration from Landskron/Lanškroun Bohemia to Wisconsin by Edward G. Langer, Nashotah, WI.

LUNCH – INCLUDED IN REGISTRATION FEE

Session Three: Jacob Sternberger: The Story of an Immigrant from German-Speaking Bohemian to Wisconsin by Antje Petty, Max Kade Institute, UW-Madison.

Session Four: Futures Trading: The Changing Landskron/Lanškroun Economy and Emigration by Diana Bigelow, Corvallis, OR.

Register Now!

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2022 – ST. WENCESLAUS DAY CELEBRATION AND TOURS OF THE CHURCH

W7911 Blue Joint Road, Waterloo WI 53594

11:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Guided tours of the church. Ask historians Edward G. Langer, James E. Kleinschmidt, and Diana Bigelow questions about the Sudeten Germans. Brats, hot beef sandwiches, homemade kolaches and other items are available in the air-conditioned meeting area.

At 2:30 an ecumenical church service will be held in the historic church officiated by the Rev. Eric Wood of the Immanuel Lutheran Church in Okawville, Illinois. He is a descendant of Joseph and Englebert Zimprich, early settlers in the Waterloo area.Good will donation.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2022 – TOURS OF THE VINCENT FALTEISEK CABIN AT THE AZTALAN MUSEUM

6264 N Highway Q, Jefferson, WI 53549

Open 12:00 noon to 4:00 p.m. The Museum also contains an artifact of the Gritzbauch family. The Aztalan Museum charges a nominal admission fee.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2022 – VISIT THE WATERLOO AREA HISTORICAL SOCIETY MUSEUM

130 E. Polk St., Waterloo, WI 53594 Open by appointment.

This museum contains artifacts of the Doleschal, Fiebiger, Fischer, Friedel, Haberman, Hiebel, Kunz, Leschinger, Lutschinger, Meitner, Peschel, Skalitzky, Zimprich, and other Sudeten German settlers. Good will donation.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2022 – VISIT THE MARSHALL AREA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

128 E Main Street, Marshall, WI 53559-0033

Open from 9:00 am until 1:00 p.m. This museum contains artifacts of the Bartosch, Blaschka, Blaska, Doleschal, Hebl, Jana, Klecker, Langer, Marek, Motl, Pirkl, Skala and other German and Czech families from northeast Bohemia. Good will donation.

Get the Sudeten German Weekend Book

On Sunday, we will have available for sale for $10 the Sudeten German Weekend Book. The book is planned to be about 75 pages in length. The book includes speech summaries, maps, a list of electronic sources, a list of hardcopy sources, museum information, a list of villages with both their German and Czech names, names and places of origin of Sudeten German settlers in southern Wisconsin and other useful information. The book is included in the registration fee for the Saturday program.

Register Today!

How we got here

The people who built and made up the congregation of St. Wenceslaus Church came to the Town of Waterloo in the mid-1840’s and early 1850’s. Some were from Germany but many came from the old Austro-Hungarian Empire province of Bohemia, part of the Czech Republic.

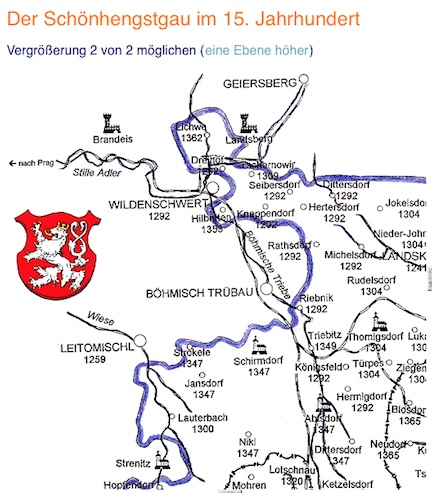

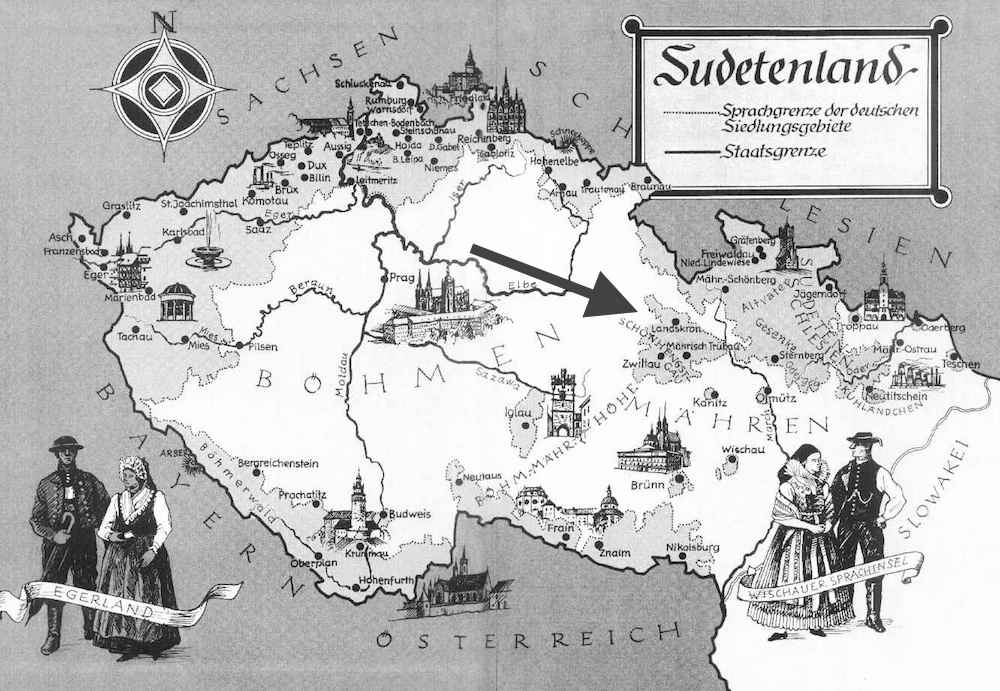

They came mostly from four tiny villages, all within walking distance of each other in a region called Landskron, about 90 miles due east of Prague. The area once was known as the Sudentenland, where German-speaking villages were sprinkled among Czech-speaking villages. Immediately after World War II, the German speakers were rounded up and exiled to Germany.

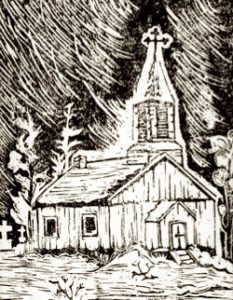

They emigrated to the United States largely after the revolutions of 1848 (coincidentally, the year of Wisconsin statehood), which brought freedom to the serfs of Europe. They bought land on “The Island” — the high ground — surrounded by the Blue Joint Marsh (especially notable due east of the church, now drained and farmed) and there established their farms and their small church of tamarack logs sheathed in board and batten. It was named after “Good King Wenceslaus,” the patron saint of Bohemia. The church measures 32 by 24 feet. The pews were built by Johann Fiedler, who is buried in the church cemetery.

The little church never had a resident pastor. It was served by priests and missionaries from both Milwaukee and Jefferson and later by the resident pastor of St.Joseph’s Church in Waterloo. Father Ivo, a Capuchin missionary from Milwaukee, baptized eight children there in 1872 and recorded that the church was known “locally as Island.” Father Huber, of Waterloo, who also served the church recorded in 1877 before returning to his native Baden for

a visit, “Closed the church of St. Wenceslaus (Island).” Regular use was discontinued in 1891.

That rendered the little church a virtual time capsule. Two men preserved the church during that interregnum: first, Henry Bartosch, and later, Joseph Fiedler, son of the builder of the church pews, who lived like a hermit on Island Church Road due south of the Church. He died in 1959.

In 1970, the Wisconsin Historical Society was constructing its outdoor pioneer village, Old World Wisconsin, outside of Eagle, in Waukesha County. The State of Wisconsin wanted to disassemble our church log by log and rebuild it there as a representative sample of that ethnic group. However, a group of citizens persuaded the bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Madison to deed the property to the Foundation in order to keep it on its historic hill. (Members are detailed in Monograph #8) The church was included on the National Register of Historic Places on May 12, 1975. The Island Church Foundation incorporated on April 23, 1976. Purchase of the church was finalized in 1977. The two-story kitchen and museum “clubhouse” was constructed in 1978 on land donated by Lester and Dorothea Fischer. The adjacent cemetery remains under the jurisdiction of the diocese.

— adapted from the nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.

They came from Bohemia in the 1840s-50s

by Edward G. Langer

Copyright 1996, Edward G. Langer, All Rights Reserved

Beginning in the early 1850s, numerous families left their ancestral villages in the provinces of Bohemia and Moravia in the Austrian Empire to start new lives. Some families moved to the German-speaking cities and towns of the Austrian Empire or the German principalities. Others traveled to distant countries such as the Russian Empire, South Africa or America. This is the story of some of these emigrants from the district of Landskron, Bohemia who decided to make new lives for themselves in the mid western United States, in particular in the state of Wisconsin.

The Old World

The district of Landskron (Czech: Lanskroun) is named after the town of Landskron. The town and district of Landskron are about 80 miles south of present day Wroclaw (Breslau) and about 115 miles north of the then-capital of the Austrian Empire, Vienna.

Landskron, the district, consisted of the town of Landskron and forty-two bordering villages. In the 1850s, Landskron-town contained about 5,000 inhabitants and was connected by rail to the rest of the Austrian Empire. Second in importance to the town of Landskron was Cermná (Böhmisch Rothwasser), a Czech village of about 3,000 inhabitants. Historically, Cermná had market rights not granted to the other villages. Cermná’s lower half was mostly Catholic and its upper half was mostly Protestant. (In 1936, it was split into two villages – Dolní Cermná and Horní Cermná). The other forty-one villages in the district of Landskron varied in size from a few hundred people to about 1,500 inhabitants. Roads connected the villages to the town of Landskron. Three-quarters of these villages were predominantly German, and the majority of both ethnic groups were of the Roman Catholic faith.

The inhabitants of these villages, both Czech and German, were divided into three broad social groups – the “large farmers” (German: Bauer, Czech: sedláci), the “small farmers” (Feldgärtner or zahradnici) and the day laborers (Taglohner or podruzi). The “large farmers” generally had farms over ten hectares (a hectare is 2.471 acres). They usually owned horses, cows and numerous smaller farm animals. These farmers were engaging in commercial farming and were able to ship produce to market in nearby towns. The “small farmers” had only a few hectares. They usually had a few cows and a number of smaller farm animals. The day laborers worked for small or large farmers as field laborers, stable hands and kitchen and house servants. In addition, some worked as weavers, carpenters, coopers or blacksmiths. Some of the day laborers, called “cottagers” (Häusler or chalupnici), owned a small house with enough land around it for a small

Typical of the Landskroner village of the era was Ober Johnsdorf (Horní Tresnovec), located just north of the town of Landskron. Ober Johnsdorf contained about 1,000 inhabitants in the 1850s, most of them German-speaking but with a significant Czech-speaking minority. The neighboring villages to the north, Cermná and Nepomuky (Nepomuk), were predominantly Czech. The other nearby villages, Jokelsdorf (Jakubovice), Michelsdorf (Ostrov), and Nieder Johnsdorf (Dolní Tresnovec), were predominantly German. Ober Johnsdorf was comprised of 1,108 hectares, which is about four and one-quarter sections of land, or 2,738 acres.

The average landholding in Ober Johnsdorf was about seven and a half hectares, with over half the farms smaller than five hectares. Only a dozen farms had more than 20 hectares. Since the town of Landskron was three miles distant, it is likely that excess grain from Ober Johnsdorf was transported by horse or ox-cart for shipment by rail to the cities of the Austrian Empire. Apart from farming, Ober Johnsdorf in the early 1850s had no church and only a basic school. For church services and any advanced schooling, Ober Johnsdorf’s villagers traveled to Landskron-town. Given the limited educational opportunities available at the time, many of Ober Johnsdorf’s inhabitants had only primitive reading and writing skills.

In sharp contrast to farming in America, Landskron-district farmsteads were not separate from its villages. Farm buildings were located on both sides of a road, and farm fields stretched straight back from the buildings until they bordered another village’s farms. Farms might also end at the woods or at an untillable hill. Generally, farmers in Ober Johnsdorf cultivated contiguous fields, unlike the practice in other areas of Europe. It could, however, be a considerable distance from the farm buildings to each farm’s property limits. Also, farmland that was wooded or low provided natural barriers separating tillable parcels within the farm.

Ober Johnsdorf’s farm buildings also showed a distinctive configuration. Generally, the living quarters were physically connected to the farm buildings. More elaborate farmsteads were set up in a U-shape or square with a courtyard in the middle. The latter square form probably developed in an attempt to provide some protection against thieves and foreign soldiers, and it also allowed the farmer to secure his animals and harvested crops from marauding animals.

The Push to Emigrate

The families of the prospective emigrants to America had lived in the Landskron district for hundreds of years. Up until 1848, the people of the district of Landskron were still subject to feudal restrictions limiting their ability to move and requiring them to provide certain services to the local ruling class. As was typical of the time, a Landskroner’s social position was determined more by birth than by personal accomplishments. In 1848, revolutions rocked much of Europe, and thereafter the Hapsburg Emperor of the Austrian Empire removed the final vestiges of feudalism. Slowly, the word spread that it was possible to emigrate.

Increased population and frequent wars were the main factors prompting the Landskroners to consider emigrating. By the mid-1800s, improved food and sanitary conditions had caused such a population explosion that there were limited opportunities for young people, and people were crammed into small one-room houses. It is estimated that in Horní Cermná there were twenty-six houses holding ten or more occupants, and four Silar families with a total of twenty-one people lived in one house in Nepomuky. There was little virgin land in the area, and subdividing the existing farms would have made them unprofitable. Further, the Austrian Empire was involved in frequent wars, resulting in increasing taxes and young men sent to fight in distant locations.

One of these wars had a direct impact on the lives of every inhabitant of the district of Landskron. In June, 1866, war broke out between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia over whether a unified Germany was to be created, what lands would be included in the new nation and which country would be the leading force of the new German nation. The Italians were a key ally of the Prussians, forcing the Austrians to fight on two fronts. Prussian General Moltke, who had learned crucial lessons on the use of telegraph and railroads from the American Civil War, was able to quickly move hundreds of thousands of Prussian troops into Bohemia. Simultaneously, hundreds of thousands of Austrian troops marched into Bohemia to meet them. Part of the Austrian army was quartered in the Landskron area, and other parts of the Austrian army marched through the area. At one point, 120,000 troops were in the Landskron area.

On July 3, 1866, the Imperial Austrian army and the Prussian army met northwest of Hradec Králové (Königgrätz), about 40 miles from Landskron. (The Battle of Königgrätz is also referred to as the Battle of Sadowa). The Prussian army was better equipped than the Austrian army. One crucial advantage was that the Prussian infantry had breech-loading “needle-guns,” enabling them to fire from the prone position at the standing Austrian infantry, which used muzzle-loaders. The Prussian victory was sudden and complete.

After the Austrian loss, some Austrian troops retreated through the Landskron area, followed closely by Prussian troops. A skirmish occurred near the villages of Rudelsdorf (Rudoltice) and Thomigsdorf (Damníkov). The encroaching armies destroyed many growing crops in their wake, and confiscated the villagers’ food as well. The Prussians occupied Landskron, and 10 to 20 soldiers took up residence in Landskroner homes. This war and the subsequent Prussian occupation had a profound effect on the Landskroners, and induced many to emigrate to America.

The New World

By the 1850s, numerous sources encouraged European peoples to emigrate to America. “How-to-emigrate” books extolled America’s virtues, especially the freedom and cheap land available in America. Rail and shipping interests made emigration sound very attractive in an attempt to increase their business. American states, such as Wisconsin, sent agents to European ports to encourage emigrants to settle in their states. Early emigrants had to rely upon these writers and businessmen for information about emigration to America, while later emigrants heard about the virtues of life in America from fellow emigrating villagers.

The first sizable emigration from the district of Landskron occurred in 1851 and consisted of Czech Protestant day laborers primarily from the villages of Cermná and Nepomuky. These emigrants had little to lose by emigrating, given their low social status in Landskron-district — they were poor, they were Czech speakers in an empire having a German ruling class, and they were Protestants in a country where the ruling class was ardently Catholic. On November 6, 1851, about seventy-four Czechs started on their trip to America. They traveled by train from stí nad Orlicí (Wildenschwert) to Hamburg. They sailed from Hamburg to Liverpool, Great Britain and then transferred to the sailing vessel Maria for the long trip to New Orleans, Louisiana. In New Orleans, they transferred to a third ship to travel to Galveston, Texas. Then they took a fourth schooner to Houston. About traveling for three or four months, fewer than half of the emigrants reached their final destination, the Cat Spring area in Austin County, Texas. Others had died along the way, of illness caused by poor food, limited water supplies and poor living conditions on the long journey. The surviving emigrants sent a number of letters home relating their ordeal, and one emigrant recommended traveling on a ship directly to Galveston even though it would be more expensive. When a second group of about eighty-five Czech Protestants left their homes for Texas on about October 9, 1853, they followed that advice and boarded the Suwa from Bremerhaven, which took them directly to Galveston. In later years, many other Czech Protestants from the district of Landskron emigrated to Texas. They were joined by some Czech and German Catholics from the district of Landskron. Some of the Czech Catholics who settled in Pierce County, Wisconsin, first traveled to Texas before settling in Wisconsin.

Already in 1852, German Catholic day laborers were applying for passports for emigration to Wisconsin. Others who indicated on their passport applications that they were bound for Texas instead headed to Wisconsin. It is not known how these applicants knew that Wisconsin was a favorable destination. However, perhaps written information of the period filtered to the tiny Landskron villages. Writers in the mid-1850s wrote favorably of life in Wisconsin, emphasizing the good farmland available, a climate similar to central Europe’s, and the presence of many German-speaking people. It is also likely that these later emigrants had learned of the tragic trip of the first Czech Protestants emigrants, and they may have decided to avoid the difficult trip to Texas.

The primary destination of the German Catholic emigres was the Watertown, Wisconsin area. In the early 1850s, Watertown, with about 5,000 inhabitants, was one of the largest cities in Wisconsin. The area’s abundant rich, rolling farmland, some of which had been partially cleared by earlier settlers, would have appealed to Landskroners wanting to farm their own land in America. Wisconsin had become a state in 1848, and southern Wisconsin was no longer considered part of the western frontier. Railroads were starting to connect the major towns in the state, and farmers were able to sell their surplus product on the market.

Watertown was also a center of German immigration. As such, the Landskron emigrants would have found in the Watertown area German-speaking immigrants from the Austrian Empire, Bavaria, Prussia and other German-speaking lands, in addition to those Landskron-district families that had emigrated in earlier years. Watertown had a German Catholic parish (Saint Henry’s) founded in 1853, a German newspaper, the Anzeiger , and a brewery.

The Voyage to the New World

Most of the earlier emigrants from the Landskron district departed from the port of Bremen in what is now northwestern Germany. The emigrants probably traveled by rail to Bremen. Landskroner emigrants to the American Midwest generally headed to the port of New York or to Baltimore. When they reached America, it is believed that most of the settlers took the train via Chicago to a town like Watertown, where they intended to look for land. If the rail lines had not yet reached their final destination, they would have completed their trip by coach or wagon.

The first Landskroner emigrants known to have settled permanently in southern Wisconsin arrived in 1852. The records of the Jason , which arrived in New York on December 7, 1852, from Bremen, shows about sixty people from the Landskron district on board: the Johann Blaschka and Johann Klecker families of Hertersdorf (Horní Houzovec), the Ignatz Yelg, Wenzel Blaschka and Johann Blaschka families of Tschernowier (Cernovír), the Joseph Veit family and Anton Wawrauscheck, Philip Zimprich and Ludwig Zimprich of Knappendorf (Knapovec), the Anton Fiebiger family of Jokelsdorf (Jakubovice), the Johann Fischer family of Riebnig (Rybník), the Joseph Zimprich family of Rathsdorf (Skuhrov) and the Wenzel Fuchs family of Hilbetten (Hylváty). Also on board were the following persons, whose place of origin may be the district of Landskron: the Wenzel Blaska and Anton Kobliz families, Barbara Detterer and Franz Meidner. The Jason provided the nucleus of the Landskroner community near what in 1859 became the village of Waterloo, west of Watertown, Wisconsin.

On January 10, 1853, the Johanna arrived in New York from Bremen with seven families of thirty-two people from the Landskron district: the John Huebel, Johann Langer and John Stangler families of Rudelsdorf (Rudoltice), the Franz Pirkl, Franz Haubenschild and Johann Haubenschild families of Triebitz (Trebovice), and the Josef Rössler family of Michelsdorf (Ostrov). Also on board was the Franz Gilg family of Nikl (Nikulec) in the neighboring county of Zwittau (Svitavy). A number of these families joined the Jason group near Waterloo, Wisconsin.

On June 17, 1853, the Oldenburg arrived in New York from Bremen, with 103 passengers from Bohemia whose stated destination was Wisconsin. The emigrants from the district of Landskron were the following: the Johann Meitner and Johann Schöberle families, Vincenz Klecker and Franz Schöberle of Ober Johnsdorf (Horní Tresnovec), the Franz Hampel, Josef Jirschele and Josef Arnold families of Rathsdorf (Skuhrov), the Franz Langer, Ignatz Huebl, and Bernhard Leschinger families of Rudelsdorf (Rudoltice), the Franz Fischer, Johann Plotz and Engelbert Habermann families of Riebnig (Rybník), the Johann Smetana and Johann Kuckera families of Tschernowier (Cernovír), the Franz Foltin family of Königsberg (Královec), and the Anton Kristl family of Michelsdorf (Ostrov). Two other families were from neighboring districts: the Wenzel Scholla family of Prívrat (Pschiwrat) and the Joseph Pospischel family of Litomysl (Leitomischl). The other families from Bohemia were the Nicholaus Dank, Johann Czernin, Johann Strilesky, and Arnold Patsch families. The Johann Meitner, Johann Schöberle, Franz Hampel and Franz Langer families, along with Vincenz Klecker and Franz Schöberle, provided the nucleus of the Landskroner community of Watertown, Wisconsin. A number of these other families joined the Waterloo community.

Ship records indicate that emigration to America was not a solitary affair by a single individual or a single family. Rather, emigrants tended to travel with others from their home district to America where they often found fellow countrymen awaiting them.

Life in the New World

When the new emigrants arrived in America, previous settlers helped them find homes, farms and jobs. The Landskroners tended to live near each other, as the later arrivals would move near their countrymen. Sometimes these later arrivals would only stay near their friends and relatives for a few months or years before moving to find cheaper land. The expanding path of these Landskron emigrants can be traced westward from Watertown toward Sun Prairie, Wisconsin and south to Janesville, Wisconsin. A significant number of Landskroners settled in Pierce County, Wisconsin, just east of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota. Both Germans and Czechs from Landskron settled in this area. The Czech community of Pierce County is still referred to today as Cherma, after their Bohemian hometown of Cermná. Other Landskroner groups settled near Owatonna, Minnesota and Casselton, North Dakota, and other emigrants settled in Illinois, Iowa, South Dakota and Oregon. It is likely that further research will discover small groups of settlers extending all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

Two examples of this migration west are the Franz Langer and Franz Jansa families. The Franz Langer family of Michelsdorf (Ostrov) is believed to be among the first to have left the Landskron area for the Watertown area. This family lived in the Watertown area from around 1852 until 1861, when they traveled west to the Plainview, Minnesota area. Later they moved to near Fargo, North Dakota. One of this family’s famous descendants is the late North Dakota Governor and United States Senator William “Wild Bill” Langer.

The Franz Jansa family from Cermná (Böhmisch Rothwasser) came to Watertown in 1867. The Jansas had brought with them only a small chest which contained some household articles and Franz’s blacksmith tools. The Jansas stayed with Mrs. Jansa’s aunt and uncle, the Johann Roffeis family, for about a week when they first arrived in Watertown, until Johann Roffeis found them a small house. To help them set up their household, Johann Roffeis gave the Jansas a dozen eggs, a sack of flour and a rolling pin. The furnishings in the Jansa house were simple: an oven, boxes for chairs, their chest and bed. The bed was a box filled with straw and covered with blankets. From these humble beginnings, Franz Jansa was able to dramatically increase his standard of living. He worked as a blacksmith in Waterloo and Marshall, Wisconsin for 11 years, saving $3,000.00, after which the Jansas moved to Cherma in Pierce County, Wisconsin and bought a farm.

Although some emigrants settled permanently in the villages and towns of the American Midwest, the majority of the emigrants wanted their own land and went into farming. In America, farms were sold in rectangular plots based upon a survey system mandated by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Generally, farms were sold in 20-acre, 40-acre, 80-acre or 160-acre parcels. Farmsteads were located at a convenient place on the farmland, and as the farms grew in size, distances between the farmers’ houses grew. Where in Landskron houses were commonly clustered together along a road, in America they were often located quite far from these roads. Farm buildings were free-standing, separate structures in America, and were not connected as in Landskron. The villages that arose were not farming villages, but rather provided a central location for tradesmen and craftsmen, along with community buildings such as a village hall, a school and a church. Where in Landskron, an hour’s walk could take you past the houses of a thousand people, such a walk in America would likely take you past the houses of only a few dozen neighbors.

Emigrants with financial means were able to afford to buy a farm shortly after their arrival in America. One of the few “large farmers” among the early Landskroner emigrants was Johann Meitner from Ober Johnsdorf. Meitner arrived in New York on the Oldenburg on June 17, 1853. On July 9 of that year, he purchased an 80-acre farm several miles north of Watertown. That fall he purchased an additional 40 acres of farmland, and in May of 1855, Meitner bought another 40 acres. None of these purchases involved a mortgage. Meitner’s resulting 160-acre farm was larger than most, if not all, of the farms in Ober Johnsdorf.

Since the overwhelming majority of these early emigrants were day laborers, they were not able to buy good land near a market town like Watertown so quickly. Their options were to save money to buy a farm, use credit, buy poorer land, or move west to find good, cheap land closer to the edge of the frontier. The poorer Landskroner emigrants used all of these methods. As noted above, Franz Jansa saved for eleven years in order to buy his farm. Johann Pitterle, a day laborer from Ober Johnsdorf who arrived in America in August, 1854, was first able to buy a farm in 1858. That year he bought an 80-acre farm north of Watertown, Wisconsin for $600.00. He bought the farm on credit at 10% interest, with $200.00 due on July 1, 1858, and $400.00 due on January 2, 1863. Many of the early emigrants to southern Wisconsin bought marshy land west of Watertown near what is now the village of Waterloo. Another early emigrant, Franz Pirkl of Triebitz (Trebovice) who arrived on the Johanna in 1853, headed to Pierce County in northwestern Wisconsin in about 1855 where land was much cheaper. His 160-acre farm was valued at $341.12 on the 1859 real estate property list.

It is logical to assume that the Landskroner emigrants spent a great deal of their social life with each other. As noted above, their adjoining farms would allow for socializing with fellow Landskron emigrants. Since most were Roman Catholic, they also attended the same church. The membership of at least three Wisconsin Catholic churches was predominantly Landskroner: “The Island” church, St. Wenceslaus, built in 1863 outside of what is now Waterloo; the Church of the Immaculate Conception, built in the early 1880s in “Lost Creek” in Pierce County, and St Martin’s Church, built in the 1890s in Cherma in Pierce County. The first two were German and the last was a Czech parish. One of the results of this social interaction is the relative frequency of Landskroner intermarriage with other Landskroners. As in the Old World, some of these marriages crossed linguistic lines, with a German-speaker marrying a Czech-speaker.

The primary cash crop raised by the early settlers was wheat. After the wheat blight destroyed the economic viability of wheat production in Wisconsin, however, the emigrants, along with their neighbors, switched to the production of milk and milk products for sale at market.

Many of the early emigrants did very well for themselves. The 80-acre farm that Johann Pitterle purchased would have made him the owner of one of the larger farms in his native village. By 1890, each of his five children owned farms near Watertown totaling 420 acres, which would have comprised about one-sixth of all the land in their native village of Ober Johnsdorf. The Pitterle children had more land in America than they ever could have dreamed of having had they remained in Europe. The success of the early emigrants induced many of their countrymen to follow them to America.

A partial listing of the family names of the Landskroner men and women who settled near Waterloo and Watertown and in Pierce County, all in Wisconsin, follows. Included in the list are their known places of origin.

The Watertown Community

The largest group of Landskroner emigrants in Watertown were from the villages of Ober and Nieder Johnsdorf (Horní and Dolní Tresnovec). Other villages represented in Watertown were Cermná (Böhmisch Rothwasser), Dittersbach (Horní Dobrouc), Lukau (Luková), Olbersdorf (Albrechtice), Rathsdorf (Skuhrov), Rudelsdorf (Rudoltice), Sichelsdorf (Zichlínek), Thomigsdorf (Damníkov) and the town of Landskron. The list of Landskroner families settling in Watertown include the following: Barrent, Bopp, Brusenbach, Clement, Dobischek, Frodel, Groh (Gro), Hampel, Heger, Huebl, Huss, Jahna (Yahna), Hecker, Hausler, Hübler, Janisch, Kalupka, Klecker, Köhler, Kohler, Kreuziger, Kunert, Kunz, Langer, Melcher, Meitner, Miller, Müller, Motl, Pfeifer, Pitterle, Richter, Roffeis, Roller, Schless, Schlinger, Schmeiser, Schöberle, Schmid, Schramm, Stadler, Stangler, Steiner, Uherr, Unzeitig, Warner, Wohlitz, Wollitz and Zeiner. Other Landskroners who lived in the Watertown area for a period of time or who married in Watertown include: Benesch, Betlach, Gritzbauch, Jansa, Kratschmer, Marek, Maresh, Markl, Nagel, Wavra, Willertin and Wurst.

The Waterloo community

Villages represented in Waterloo include Cermná (Böhmisch Rothwasser), Dreihöf (Oldrichovice) Hertersdorf (Horní Houzovec), Jokelsdorf (Jakubovice), Knappendorf (Knapovec), Michelsdorf (Ostrov), Rathsdorf (Skuhrov), Riebnig (Rybník), Rudelsdorf (Rudoltice), Tschernowier (Cernovír) and Zohsee (Sázava). The list of Landskroner families settling in Waterloo include the following: Barta, Bartosch, Benisch, Betlach, Binstock (Binenstock), Blaschka, Fiebiger, Filg, Haberman, Huebel, Jahna, Janisch, Klecker, Koblitz, Langer, Leschinger, Maresch (Mares), Mautz, Melchior, Miller, Motl, Neugebau, Peschel, Pitterle (Peterle), Rotter, Tilg (Yelg), Tomscha, Schieck, Schiller, Skalitzky (Skalitzka), Springer, Stangler, Veith, Wovra, Wurst, Zalmanová and Zimbrich (Zimprick).

The Pierce County Landskroners

Although Franz Pirkl settled in Pierce County in 1855, most of the Landskroner emigrants to Pierce County arrived after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Many of these emigrants, both German and Czech, passed through Waterloo or Watertown on their way to Pierce County. Many Czech emigrants from Cermná (Böhmisch Rothwasser) settled here. Some Czechs traveled through Texas and not the Waterloo and Watertown areas. Other emigrants came from the villages of Hermanice (Hermanitz), Jokelsdorf (Jakubovice), Michelsdorf (Ostrov), Ober and Nieder Johnsdorf (Horní and Dolní Tresnovec) and Sichelsdorf (Zichlínek). Among the Landskroner families eventually settling in Pierce County were the following: Appel, Benes, Brickner, Falteisek, Fischer, Gregor, Heinz, Huebl, Jahna (Yahna), Jana (Yana), Janisch (Yanisch), Janovec, Jansa, Kabarle, Katzer, Kitna, Klecker, Kreuziger, Kusilek, Langer, Marek, Maresch, Maresh, Meixner, Merta, Motl, Nagle, Neugebauer, Nickel (Nicol), Novak, Pechácek, Pelzel, Prokscher, Raeschler, Richter, Roller, Schmeiser, Schmied, Schöberle, Seifert, Steiner, Strofus, Svec, Tajerle, Tayerle and Yanovec.

Conclusion

The emigrants from Landskron to Wisconsin, both German and Czech, found the land and the freedom they desired and generally were able to attain a much higher standard of living than their relatives who remained behind in Landskron. They were also able to escape the horrors of war, Nazi rule, forced expulsion, collectivization and Communist rule that marked the lives of the Germans and Czechs who did not emigrate.

Sources

Sources used in writing this article include vital records, probate records, census records, farm abstracts, plat maps, cadastral maps, passport applications, ship manifests, naturalization records, church records, cemetery records, obituaries, local histories and personal histories. I visited the regional archives in Zámrsk on two occasions. Many interviews were conducted over the years. Three interviewees worth noting for their assistance are Frantisek Silar and Rev. Miroslav Hejl of Horní Cermná and Otto Cejnar of Dolní Cermná. Invaluable sources of information on the Pierce County immigrants are Volumes Seven and Eight of Pierce County’s Heritage. German language sources include the Schönhengster Heimat, Schönhengster Jahrbuch, “Der Bauernhof des Schönhengster Oberlandes” by Johann Neubauer (Schönhengster Heimatbund 1989), “Landwirtshaft im Schönhengstgau” by Albin Ruth (Schönhengster Heimatbund 1988) and “Heimat Kreis Landskron” by Franz J. C. Gauglitz (Verlagsdruckerei Otto W. Zluhan 1978)

Edward G. Langer

Bio

I am the 13th of 14 children of a Wisconsin dairy farmer and a Swiss immigrant mother. My father’s ancestors are from the district of Landskron/Lanskroun, Bohemia and my mother was born in Küsnacht, Kanton Zürich, Switzerland. I have been to Landskron/Lanskroun five times. I have a B. A., magna cum laude, in Government from Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin and a J.D., cum laude, from the University of Wisconsin Law School. I am Assistant District Counsel for the Internal Revenue Service in Milwaukee. I have been researching local history and genealogy for over 30 years. My wife and I traveled to my grandfather’s hometown in Switzerland to get married. I am proficient in German, but not Czech.

In the Landskron region, Hertersdorf (now Horni Houzevec) was founded in 1292; this was photographed in 1942.

This little church in Hertersdorf was built in 1800 and still stands. It is the Holzkirchlein visitation of the Virgin Mary.

Typical construction in the region, a barn connected to the house; this was photographed in 1910.